eBPF: concepts and C programs with libbpf and bpftool

Published on: November 30, 2025

11 min read

Content

- ▶ Introduction

- ✏️ A brief overview and why write eBPF programs using C?

- 🧩 Essential components of eBPF

- 📜 libbpf and bpftool

- 🇨 First eBPF Program in C

- 🧑💻 Practical Example of eBPF in C

- ✅ Use Cases

- ✨ Conclusion

- 📚 Bibliography and Recommended Resources

▶ Introduction

In the article Learning eBPF for Observability, Optimization, and Security we explored basic concepts of eBPF, and we wrote some basic examples in Python using BCC. In this article, we continue to discover the potential of eBPF by understanding a bit more about the attachment points or (hooks) availables in eBPF that are associated with different types of programs that can be executed in the kernel space, helper functions and eBPF maps. Then we will study the libbpf library and the bpftool utility that will help us to write and load eBPF programs in C in the kernel space. But before:✏️ A brief overview and why write eBPF programs using C?

eBPF allows us to expand the kernel’s functionalities at runtime through libraries and tools that help us to write, load and execute programs in the kernel level without modifying the kernel source code or adding modules. Programs eBPF can be attached at various points with the kernel for different purposes such as collecting information, modifying data, and making real-time decisions to respond to security threats, among others. One of the tools we use to compile and execute eBPF programs is BCC, which, due to its ease of use, is a good tool for quickly prototyping and exploring, but it involves a runtime overhead and abstracts away certain steps of the process that are good to know.

I choose the C language for this tutorial for two main reasons: the first is personal, I like embedded systems, and the dominant language in that field is C, the second is that the libbpf, Linux kernel, git and many other important tools use C. Programmind languages are tools, each more useful for some cases than for others, in this point eBPF has a great potential in having a development environment for different programming languages like Rust, Go, Python, Java, C/C++, that makes it easier to work in different areas. With this in mind, let’s review some important points of the eBPF technology.

🧩 Essential components of eBPF

Some of the essential components of eBPF are: the virtual machine integrated into the Linux kernel, the verifier that ensures the security of the program before loading it, the JIT compiler (Just-In-Time), the attachment points (hooks), the helper functions and the eBPF maps, among others. In this article, we will focus on the following:Attachment Points (Hooks) and eBPF Program Types

The hooks are points in the kernel where eBPF programs can be attached to execute when the kernel reaches the hook. These points or hooks are associated with different events such as: network events, system calls, kernel tracepoints, hardware events, among others, even it is possible to create custom hooks.Helper Functions

Because eBPF programs are limited and are restricted by the verifier to prevent breaking the system exist the helper functions, a set of functions in C defined by the kernel that form an internal API between the eBPF programs and the kernel. For instance, there are helper functions to print messages, manipulate network packets, monitor the system, interact with eBPF maps, among others. To see a list of helper functions organized by type you can visit this link eBPF Docs. Helper functions Or see the full list in the man page list of eBPF helper functions.eBPF Maps

Maps are the way eBPF programms communicate between each other in the kernel space and with the user space, there are generic maps for different use cases, maps to keep references to other maps, maps to transmit large amounts of information between the kernel and the user space, maps to facilitate the redirection of network packets between devices, among others. You can see a list of available maps in: Map types (Linux)📜 libbpf and bpftool

libbpf is a C library that acts as the eBPF loader in the kernel, its main function is to take the compiled eBPF files, manage the loading, verification as well as attaching and removing the programs from the hooks. It also includes support for the CO-RE (Compile Once - Run Everywhere) principle, which enables the portability of eBPF programs; libbpf offers support for the BPF skeleton generated by the bpftool utility enabling the creation and manipulation of eBPF programs an applications in C.An eBPF application consists of one or more eBPF programs, maps, and global variables. All of this is coordinated through the libbpf API by manipulating the programs and executing them in different phases of their lifecycle. The eBPF program lifecycle is as follows: opening, loading, attaching, and detaching.

bpftool is a command-line tool known as the Swiss Army knife of eBPF, it allows to load, manage, and manipulate eBPF programs in the kernel space, this tool uses the libbpf library and is fundamental to generate the headers vmlinux.h and the eBPF skeletons used to write eBPF programs in C.

Example: to see which eBPF programs are loaded in the Linux kernel with detailed information:

sudo bpftool prog list🇨 First eBPF Program in C

Remember that eBPF programs are composed of two parts: the user space program and the kernel space program which is the part that will be loaded and executed inside the Linux kernel when a specific event occurs. Using an example from thelibbpf-sample repository, we are going to write our first user space eBPF program in C, with the help of libbpf for the program’s lifecycle, that is, to open it, load it and attach it to the hook. Create an empty folder for the example, and inside it, create a file named exec.c with the following code:#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <sys/resource.h>

#include "exec.skel.h"

static void bump_memlock_rlimit(void)

{

struct rlimit rlim_new = {

.rlim_cur = RLIM_INFINITY,

.rlim_max = RLIM_INFINITY,

};

if (setrlimit(RLIMIT_MEMLOCK, &rlim_new)) {

fprintf(stderr, "Failed to increase RLIMIT_MEMLOCK limit!\n");

exit(1);

}

}

int main(void)

{

bump_memlock_rlimit();

struct exec *skel = exec__open();

exec__load(skel);

exec__attach(skel);

for(;;) {

}

return 0;

}Now let’s write our first code for the kernel space. In the same folder, create another file called exec.bpf.c

#include "vmlinux.h"

#include <bpf/bpf_helpers.h>

SEC("tp/syscalls/sys_enter_execve")

int handle_execve(void *ctx)

{

bpf_printk("Exec Called\n");

return 0;

}

char LICENSE[] SEC("license") = "GPL";Let’s briefly review the programs before continuing: in the exec.c code we included the exec.skel.h skeleton file which we will generate using bpftool. We also see the bump_memlock_rlimit(); function which was necessary in versions of the kernel prior to v5.11 to increase the memory lock limit for the eBPF maps and buffers, from v5.11 onwards this is optional since the new way to increase resources is through the memory.max configuration of the cGroup which is part of the process that creates it. In the exec.bpf.c code we included the vmlinux.h header which we also need to generate using bpftool. Now that we have both files, we follow the compilation and execution steps as follows:

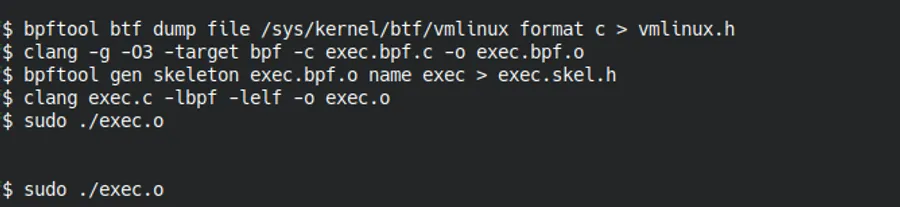

- Generate the vmlinux.h file with bpftool:

bpftool btf dump file /sys/kernel/btf/vmlinux format c > vmlinux.hThis file provides us with a complete collection of the structures and data types of the running kernel; it does this by reading and processing the BPF Type Format (BTF) information. This collection allows the eBPF programs we write in C to safely access the kernel’s internal structures, such as task_struct, and spares us the need to manually include many Linux headers.

- Compile the program for the kernel:

Using the Clang/LLVM compiler, we transform the exec.bpf.c program into eBPF bytecode inside an ELF file, or in this case, a .o file. We do this with the command:

clang -g -O3 -target bpf -c exec.bpf.c -o exec.bpf.o💡 The compiler option -D__TARGET_ARG_xxx allows cross-compilation, for example to use eBPF in embedded systems.

- Generate the skeleton:

bpftool gen skeleton exec.bpf.o name exec > exec.skel.hUsing bpftool, the object file is taken to generate the exec.skel.h skeleton, which will contain the necessary structures and functions such as exec__open(), exec__load(skel), exec__attach(skel), at this point the exec.skel.o file is no longer needed and can be deleted.

- Compile the user space program:

The file is converted into an executable linked with the libbpf library using clang or gcc; compilation is normal here.

clang exec.c -lbpf -lelf -o exec.o27 / 5.000 The program runs with:

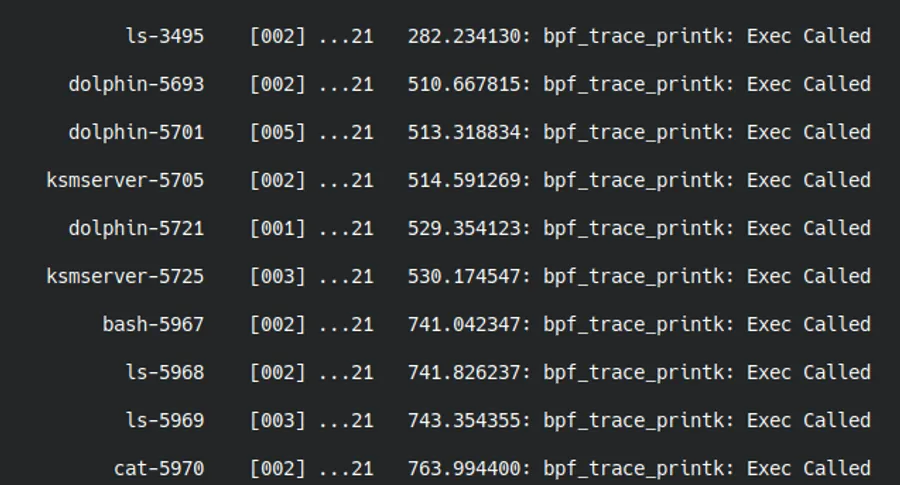

sudo ./exec.oYou can view the output at another terminal with:

sudo cat /sys/kernel/tracing/trace_pipeTo stop, press Ctrl+C on both terminals.

Terminal showing the output of the eBPF program capturing calls to execve.

🧑💻 Practical Example of eBPF in C

Now, we are going to write a more practical eBPF program that, instead of printing a message with bpf_printk() uses ring buffers to transmit information like the name and PID of the process that is triggering the hook associated with the correct execution of a program. Let’s create a new folder with the files exec.c and exec.bpf.c. like this:exec.c

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <signal.h>

#include <sys/resource.h>

#include <bpf/libbpf.h>

#include "exec.h"

#include "exec.skel.h"

static volatile bool exiting = false;

static int handle_event(void *ctx, void *data, size_t data_sz)

{

const struct exec_evt *e = data;

printf("Process executed: %-16s (PID: %d)\n", e->comm, e->pid);

return 0;

}

static int bump_memlock_rlimit(void)

{

struct rlimit rlim_new = {

.rlim_cur = RLIM_INFINITY,

.rlim_max = RLIM_INFINITY,

};

if (setrlimit(RLIMIT_MEMLOCK, &rlim_new)) {

fprintf(stderr, "Failed to increase RLIMIT_MEMLOCK limit!\n");

return -1;

}

return 0;

}

int main(void)

{

bump_memlock_rlimit();

struct exec *skel = exec__open();

exec__load(skel);

exec__attach(skel);

struct ring_buffer *rb = ring_buffer__new(bpf_map__fd(skel->maps.rb), handle_event, NULL, NULL);

for(;;) {

ring_buffer__poll(rb, 1000);

}

return 0;

}exec.bpf.c

#include "vmlinux.h"

#include <bpf/bpf_helpers.h>

#include <bpf/bpf_tracing.h>

#include "exec.h"

char LICENSE[] SEC("license") = "Dual BSD/GPL";

// Ring Buffer (256KB)

struct {

__uint(type, BPF_MAP_TYPE_RINGBUF);

__uint(max_entries, 256 * 1024);

} rb SEC(".maps");

// Hook

SEC("tp/sched/sched_process_exec")

int handle_exec(struct trace_event_raw_sched_process_exec *ctx)

{

struct exec_evt *e;

// Ring buffer size reserve

e = bpf_ringbuf_reserve(&rb, sizeof(*e), 0);

if (!e)

return 0;

// Event

e->pid = bpf_get_current_pid_tgid() >> 32; // TGID (user PID)

bpf_get_current_comm(&e->comm, sizeof(e->comm)); // name of the process

bpf_ringbuf_submit(e, 0); // transmit to user space

return 0;

}

Terminal showing the four steps of eBPF compilation: generating vmlinux.h, compiling to bytecode, generating the skeleton, and compiling the final executable.

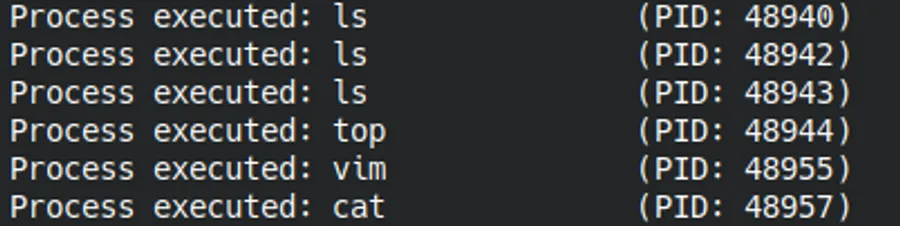

Repeat the compilation and execution stages of the first example. When executed in the terminal, it shows in real-time all successfully created processes, including their name and PID. You can open new terminals, execute commands like ls, cat, vim, or any other program and you will see how the eBPF program immediately captures every call to the scheduler’s tracepoint that is activated each time execve() is successfully executed. To stop the execution, press Ctrl+C. This example demonstrates how ring buffers enable efficient communication between the kernel space and the user space, making it a fundamental technique for system monitoring and auditing tools in production.

Real-time capture of executed processes through the scheduler hook sched_process_exec

✅ Use Cases

The eBPF ecosystem features open-source projects such as:- Cilium: a specialized project for the network, security, and observability for cloud-native environments, such as Kubernetes and others. It uses eBPF to inject control logic, load balancing, encryption, and additional security capabilities directly into the kernel.

- Parca: an open-source project to perform continuous profiling. It uses eBPF to collect program profiles (CPU, memory, I/O, etc.) in production environments and stores them to allow for queries and performance analysis.

There are other projects, and although we often use eBPF through interfaces that make our work easier and faster, it is good to understand how the technology works to get the most out of it

✨ Conclusion

In this exploration of eBPF in the C language, we covered several key concepts such as the attachment points or hooks, helper functions, and eBPF maps. We also wrote basic and practical examples that allowed us to understand the workflow: generating the vmlinux headers and the exec.skel.h skeleton for our examples using the bpftool utility, generating the bytecode for the kernel, compiling the user-space program using clang, and executing it to view the output in the terminal. By using the C language, we can more directly explore the libbpf library, besides opening the possibility of using eBPF in embedded systems through cross-compilation.

The eBPF ecosystem continues to evolve and expand. We have seen some possibilities and use cases: network monitoring, creating secure networks, performance analysis, and implementing real-time security policies. In the next article, we will delve into profiling techniques using perf and eBPF to analyze the behavior of our applications using flamegraphs, which allows us to identify bottlenecks and optimize system performance.

I encourage you to modify the examples presented, explore different hooks, and try different types of maps. Every program you write will bring you closer to understanding the true power of this technology.